The scene is Melbourne in 1865, during the latter stages of the American Civil War. Colonists had been eager for news of the schism between two groups they saw as their close relatives. Their great distance from the conflict did nothing to dampen interest in what was happening on the other side of the world, and perhaps even served to magnify it.

As a British colony, Victoria had adopted a policy of strict neutrality towards the warring parties in America, but that policy hadn’t really been tested. In Britain, the upper classes tended to support the South, especially at first, as the North was seen to be fighting to establish its own empire. Others saw the cause of the North as about freedom, especially for slaves. But some saw the cause of the South as having parallels with the Eureka Stockade uprising and the aspirations of colonists for self-government.

On 25 January 1865, a combination steamship and sailboat calling itself the Shenandoah and flying the 13-star Confederate flag came through Port Phillip heads. The pilot station at Queenscliff notified officials in Melbourne by telegram and news got around quickly. By the evening, as the Shenandoah dropped anchor off Sandridge pier (now Port Melbourne), she was rapidly surrounded by a flotilla of small boats, while hundreds of people watched from the shore.

The Captain, a dashing and somewhat aloof man named James Waddell, sent Lieutenant Grimball ashore to present himself and a letter to the Governor, Sir Charles Darling, in Toorak, requesting that the ship be allowed to make repairs to a propeller shaft, and to take on coal and provisions. The Governor consented, as this was within the rules of neutrality.

Over the next few days, the Shenandoah became a major attraction. The Hobson’s Bay Railway Company put on special trains over the weekend to take thousands of sightseers down to Sandridge (on what is now the Port Melbourne/Beacon Cove light rail).

What we might call the “tabloid” or gossip press of the day were all over the officers:

The men are a fine and determined looking asset of fellows.” (The Herald)

“They are dashing fellows and seem to take a great pride in their flag and in their fine ship.” (Illustrated Australian News)

Captain Waddell is a six-foot North Carolinian with thick black hair and a weather-beaten face, the colour of deep mahogany. He limps slightly from a dueling wound which he never discusses. … a gentleman of most prepossessing appearance and bears about him the frank expression of a sailor.” (Illustrated Melbourne Post)

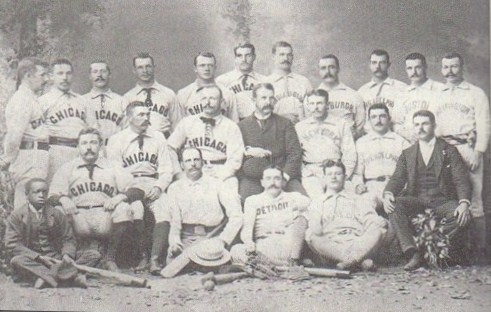

Yes, the Confederate officers made a great impression. Many of Melbourne’s young men rapidly converted their British-style full beards to the “Colonel Sanders” style moustache and tuft favoured by the Southern gentlemen.

Some of the officers moved into Scott’s Hotel in Collins Street – where they were generally well-received, although a fight or two did break out – and they were seen at the Theatre Royal and occasionally in the vicinity of Mother Fraser’s brothel in Stephen Street (now Exhibition Street).

They apparently also enjoyed a drink on board. As well as asking for fresh meat, vegetables and bread, Waddell also requested “sea supplies” including “brandy, rum, champagne, port, sherry, [and] beer”.

The officers attended a ball staged in their honour at Craig’s Royal Hotel in Ballarat and – rather controversially – they were guests at a special dinner at the exclusive Melbourne Club, attended by about 60 of Melbourne’s leading citizens, including (as The Age reported) Judges of the Supreme Court, politicians, public servants and senior police.

Governor Darling soon found it increasingly difficult to justify the welcome and assistance being given to the Shenandoah. Firstly, there was pretty clear evidence that the Shenandoah was actually a British merchant ship called the Sea King, which a Confederate agent had purchased under false pretences, and then Waddell had modified and armed in a Spanish port. Visitors to the ship at Sandridge could still see remnants of the words “Sea King” on the bow and on many other fittings – even on the cutlery in the Officers’ Mess. The crew were the very definition of motley – hardly an American among them.

There was a strong argument that, as the Shenandoah had never been to a Confederate port, she didn’t actually qualify as a Confederate ship, was therefore not entitled to the usual courtesies extended to a “belligerent” and could even be liable to seizure on behalf of the British government.

Then there was the Shenandoah’s track record. It emerged that the ship had raided up to a dozen Northern ships, or ships carrying cargo from the North, at sea in the Atlantic and Indian oceans on its way from European waters to Melbourne. Several of the vessels had been burned, theirs crews put ashore in foreign ports and the officers and their wives taken prisoner, while others had been “ransomed” for tens of thousands of pounds.

In contrast to the hero-worshipping gossip newspapers, The Age took a stern view of the Shenandoah’s activities:

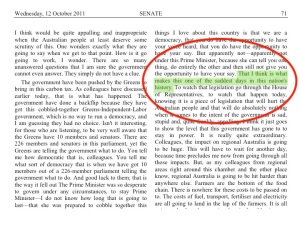

We cannot regard the Shenandoah as other than a marauding craft, and her officers and crew than as a gang of respectable pirates. (She) is built for running away from anything more powerful than herself and for overtaking heavily laden and peacefully voyaging ships of the American Republic. Her vocation is not to fight, but to plunder; not to shed the blood of her crew in their country’s defence, but to fill their pockets with prize money.

A group of prisoners from the Shenandoah turned up in the office of the US Consul to Melbourne, William Blanchard: they were the captain and crew as well as the Captain’s wife and son, from a merchant ship called the Delphine which Waddell had raided and burned in the Indian Ocean. Blanchard began sending a barrage of letters to the Governor and other officials claiming that the Shenandoah was nothing more than a pirate ship and demanding that it be seized. Then there was the case of “Charley”, a local Melburnian who was found on board the Shenandoah while still in port, having signed on as a cook. Recruiting crew in a neutral port was strictly against the agreed terms of neutrality.

Finally, under great pressure from Blanchard and critics like The Age, Governor Darling was forced to act. He sent troops to the Williamstown dry dock where the Shenandoah was undergoing repairs and had the ship surrounded, ensuring that no assistance could be given and that no locals could go aboard.

After Waddell gave an assurance that he was not recruiting or enlisting crew, the seizure was lifted, the Shenandoah was refloated and Waddell was instructed to leave port at the earliest opportunity. Reports surfaced of up to 70 local men having been rowed out to the ship at various times under cover of darkness, but after the Shenandoah sailed out of Port Phillip on the 18th of February, 42 “stowaways” were “found on board” and enlisted as crew. From Victoria, she steamed north and continued to wage “war” on Union merchant shipping, and especially the whaling fleet in the North Pacific.

Clearly the men recruited in Melbourne – almost all of whom were not “Australians” but from a variety of countries, probably having been in Victoria to try their luck on the goldfields – were of great assistance in the ship’s further activities. And even after the South surrendered, the Shenandoah continued its depradations for several months, Waddell claiming later that he had not yet received official orders to stand down.

Eventually, after the dust of the Civil War had settled, an international tribunal found that the British government had breached the rules of neutrality by permitting Waddell to recruit personnel in Melbourne, and awarded damages to the United States of around 800,000 pounds, a hefty sum indeed for the times.

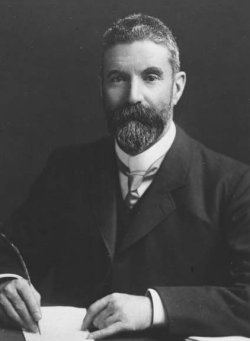

Not much physical evidence remains of the Shenandoah’s sensational visit to Melbourne in 1865, although one intriguing mystery continues. One of the people said to have entertained Waddell and his officers was a Scottish stonemason and builder named Samuel Amess (as in Amess Street, North Carlton), who had built the Treasury building in Spring Street and Customs House in Flinders Street, among other fine public buildings, and was in the process of constructing the Kew Lunatic Asylum. He was a Melbourne City Councillor at the time of the Shenandoah’s visit and later served as Lord Mayor.

In the 1870s, Samuel Amess bought Churchill Island in Westernport Bay, and there he installed a cannon that family tradition says was given to Samuel by Captain Waddell in recognition of his hospitality. The cannon is still there, but Civil War and cannon buffs now say there’s no way it could be from the Shenandoah… but no-one has been able to say where it did come from, if not from the rebel vessel.

Sources and further reading: Pearl, Cyril (1970). “Rebel Down Under: When The Shenandoah Shook Melbourne, 1865.” Heinemann.

Sources and further reading: Pearl, Cyril (1970). “Rebel Down Under: When The Shenandoah Shook Melbourne, 1865.” Heinemann.